What was Helen weaving and the importance of other storytelling methods

How marginalised communities told stories beyond words.

Over the weekend, I was invited to share some of my research and writing at aNERDgallery. Since what I shared was only the tip of my research iceberg, I thought I’ll post it here as a full article.

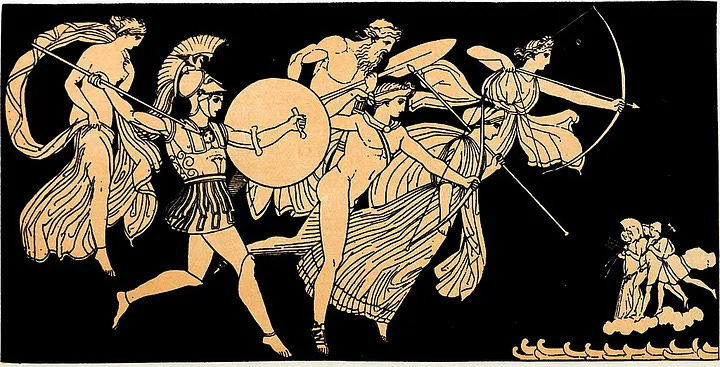

We’ve all heard of Helen of Troy or perhaps, Helen of Sparta, and we all probably know of her beauty, being the face who “launched a thousand ships”. Those familiar with Homer and Greek Antiquity may also add that she, a queen in her own right, had allegedly “caused” the Trojan War as those ships were after all launched so as to get her back from Troy after Paris had abducted her. This account of the story however undermines her agency, her voice and her telling of her own story.

Beyond the so-called role she played in the decade-long war, an often-overlooked aspect of Helen’s role in Homer’s epic poem was how her first appearance therein shows her engaged in the act of weaving.

“[Iris] came on Helen in the chamber: she was weaving a great web, a double folded cloak of crimson, and working into it the numerous struggles of Trojans, breakers of horses, and bronze-armoured Achaeans, struggles that they endured for her sake at the hands of the war god.”

The Iliad, Book 3

Herein, her capabilities are further emphasised by how she was shown weaving a “double-folded cloak of crimson” whereby its double-fold makes it a highly technical piece that is challenging to make. As such, even though the discourse surrounding Helen emphasizes her beauty and how she must be possessed, they obscure how she is a skilled weaver who is both able and willing to use her own skills.

It is important to note that Helen here is working on a tapestry such that she herself is also telling her own version of the story through the cloak she weaves. Of note here is the depiction of Helen through ekphrasis — being, the use of detailed description of a work of visual art as a literary device. This makes it clear that as Helen takes on the position of a bard who is working in a visual medium as opposed to oral verse, we can also see within the words of The Iliad a hint towards the gaps within the known myth, being Helen’s own untold story of the Trojan War. After all, the marginalised seldom had the privilege of accessing the scribbles and scrawls that we are so familiar with. As a response to their circumstances, they often had to tell stories in their own unique ways.

The Iliad builds upon this gap by showing how starkly different Helen’s story was from the stories told about her by the rest of the men. Even though she acknowledges that the armies were fighting for her, she retorts Homer’s blaming of her by attributing their sufferings to Ares, the god of war.

Between a god and a beautiful woman, whose story do we believe? As Helen neither returns to her weaving nor is the historical web mentioned again, questions arise as to whether the image of war she had created in The Iliad is literal or metaphorical.

Either way, is it even possible to ascertain the truth behind Helen’s claim when her story is told through a textile artefact that must be seen and felt in order to be truly understood, an elusive artefact that we never had access to? Can we even believe Homer’s claim as to what Helen is doing? Considering how Homer who tells the story of the Iliad is also supposedly blind or not a real person altogether, the impossibility of grasping Helen’s story through words alone is emphasised.

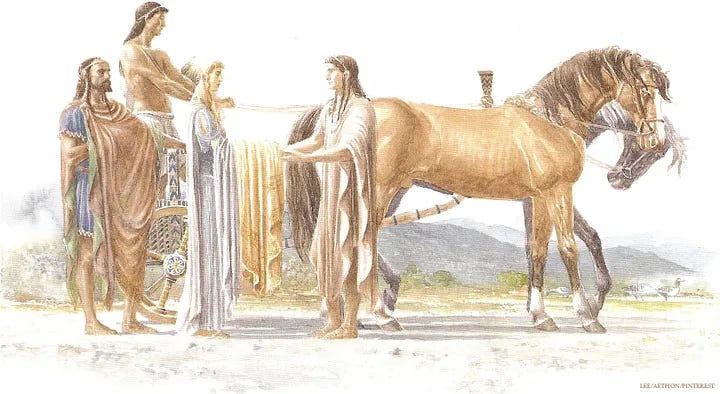

Beyond The Iliad, Helen also demonstrates the the significance of textiles to female narratives in The Odyssey as she gifts Telemachus with a cloak while mentioning the potential for handcrafted objects to immortalize those who have made them.

“And I too, dear child, have this gift to you, a monument to the hands of Helen, for your wife to wear, on the day of her very lovely wedding”

The Odyssey, Book 15

Aside from transgressing upon her husband’s position by bestowing upon Telemachus the last gift, a position which suggests that her gift is the best or most important, she also outdoes him for this cloak is the only garment in either epic to have its commemorative function expressly articulated. This is crucial as her gift is also a medium of exchange between her and another woman, demonstrating her capacity to navigate invisibly through the gaps within the established structures of power in order to create connections, not through texts, but textiles.

In considering both depictions of Helen together, the doubleness of her hands — possessed of the skill to commemorate and to destroy — may be observed. Even though these aspects of Helen are often downplayed or undermined, the power she wields as a female character in both of the Homeric texts cannot be ignored.

Instead of seeing Helen as nothing more than a pretty face, her presence as a charged figure who amplifies marginalised voices. Less more of such stories get lost through time, we should start paying closer attention to the different ways by which narratives are constructed.